Are you sure Afterpay is a disruptive company? What about Apple, Uber and Tesla? (hint: only one of them is actually disruptive)

Deep dive of the Disruption theory, how it got disrupted and how it still remains relevant

Prof.Clay Christensen was not impressed with how people were disrupting his Disruption theory

Clay Christensen was a Harvard Business School professor, an academic, a business consultant and an overall strategy titan. He’s acknowledged as one of the most influential business thinkers of the last 50 years impacting the worldview of industry giants like Andy Grove, Steve Jobs, Bill Gates and Michael Bloomberg.

He’s best known for his work on disruptive innovation and answering the question: What leads to giant companies being defeated by disruptive competitors. In doing so, he brought the word “disruption” into the corporate and business lexicon.

Of course, when he published The Innovator’s Dilemma in 1997, even he would not have anticipated how much the phrase “disruptive innovation” would takeover business jargon.

In fact, he had to write another paper for the Harvard Business Review clarifying the whole mess in 2015.

Here’s the prognosis from the man himself.

Unfortunately, disruption theory is in danger of becoming a victim of its own success. Despite broad dissemination, the theory’s core concepts have been widely misunderstood and its basic tenets frequently misapplied.….In our experience, too many people who speak of “disruption” have not read a serious book or article on the subject. Too frequently, they use the term loosely to invoke the concept of innovation in support of whatever it is they wish to do. Many researchers, writers, and consultants use “disruptive innovation” to describe any situation in which an industry is shaken up and previously successful incumbents stumble. But that’s much too broad a usage.

That last statement is what we are trying to understand as well - what situation qualifies to be called “disruptive innovation”?

Before we get to understand that. You are probably wondering - why does it matter so much? What’s in a name?

Actually, it matters very much, think of it as a doctor correctly identifying a disease. If you are feeling a bit feverish, the doctor can’t just assume it to be the most popular virus going around, can she? The correct diagnosis will determine the correct treatment. Here’s the Prof’s summary

Disruption is a theory of competitive response. It tells you: if I innovate in this way, then this is what I can expect incumbent competitors to do. If I introduce a sustaining innovation, incumbents will generally try to mount a defense and try to eliminate me. If it’s disruptive innovation, they are likely to ignore me or flee rather than fight

Let’s first understand the theory with the classic example

Prof.Christensen started off trying to answer - Why do so many big and powerful companies lose their leadership position and become relegated to the sidelines? Why is success so hard to sustain?

Through his research across multiple industries, he identified that incumbents outperformed entrants in a “sustaining innovation” context but underperformed in a “disruptive innovation” context.

In other words, a company’s odds of beating the incumbent were significantly better if their products/services were ‘disruptive’ rather than ‘sustaining’.

Here is a short summary of how disruptive vs sustaining innovation is envisioned

The classic example that Prof.Christensen used to explain disruptive innovation was steel mini mill.

Context: In the 1970s, the steel industry was tiered, the low-end, low-margin product was a concrete reinforcing bar (rebar), and the high-end, high-margin product was sheet steel. The industry was being served by integrated steel mills which manufactured all the products.

Catalyst: Steel mini-mills entered the market. These mini-mills initially had crude manufacturing capability and could only make rebars. The customers of rebars were non-fussy, since once the rebars were buried in the cement, it couldn’t be verified anyway. The key thing about mini-mills though was that they could make the product at a twenty per cent lower cost.

Reaction: The incumbent integrated steel mills were quite happy to give up market share in the low-end, low-margin rebar product. The rationale being - let’s move to the high margin products and leave this to these unsophisticated mini-mills. As a result, mini-mills kept increasing capacity as the integrated mills kept shutting the rebar lines. As a bonus, the integrated mills got to report higher gross margins too. Imagine you are the CEO of an integrated mill. You’re showing good revenue growth and fabulous margin growth. What’s not to like?

Conclusion: The issue was that the mini-mills slowly rose up the value chain. With integrated mills exiting the rebar market, mini-mills were only competing against other mini-mills. This brought the price in the rebar market further down. The only way for mini-mills to survive was then to do the one thing integrated mills never thought was possible - they moved upmarket and started offering better quality, higher-margin products. Eventually, mini-mills kept their cost advantage, learned to manufacture high-end, high-margin products and finally drove the integrated mills out of business.

The large, profitable, quality-conscious incumbent Goliath had been defeated by a bunch of scrappy, low-quality mini-mill Davids.

This example convinced Andy Grove to launch the Celeron chip - a product targeted at the lower end of the market, disrupting Intel’s own premium product line in 1997. Within a year Celeron had captured 35% of the market!

Why do incumbents willingly let this happen?

Prof.Christensen understood the incumbents ‘rational’ behaviour to focus on their high-end customers and products. One reason identified by him for this behaviour was the focus on wrong metrics to measure success. Ratios like return on assets, gross margins percentage, IRRs make it difficult for incumbent managers to rake on risks which might affect these ratios in the short-term.

In addition, the Prof also posited two more ideas

Understand what job consumers want to hire a product to do. As long as a product or service is getting that job done, the consumers will keep using the product. Think of Ikea - it’s hired to do a job - furnish my apartment quickly and for a low cost. Prof. Christensen called this the job-to-be-done (JTBD)

Over the long term, modular products which have standardised components, optimised for price and speed will beat integrated products which have unique components which are optimised for function and reliability. Think of the PCs - initially all the systems (except the software) were manufactured by IBM, they were the market leaders. Eventually, the whole system was modularised with individual components being standardised. Just think of how you can ‘build a PC’ on the Dell website.

In the mini-mills example, the incumbents were focussed on protecting their share in the high-end sheet metal market by offering better products (sustaining innovation). However, they got taken out by mini-mills who used cheap, modular, good-enough technology which got the job done. Disruption - enter, stage right.

Here is a summary by Alex Danco (who’s gift is the ability to convey complex strategy in a simple sentence) of Prof.Christensen’s three ideas

Consumers know what jobs they want done, and they’re going to hire products that get that job done as cheaply and effectively as possible. High-end incumbents with integrated products often fail to recognize or are unable to respond to the threat posed by lower-end, modular competitors who can solve users’ needs

Alright, now we know what is Disruption theory.

Is it universally applicable? Let’s find out

Let’s look for examples where the theory failed. Settle in, we are taking the scenic route.

Unfortunately, the disruption theory has failed to account for some really famous companies

Let’s see if you can guess which companies the Prof is referring to in the below quote from a June 2007 interview

The “X” is a sustaining technology relative to “Y”. In other words, “ABC” is leaping ahead on the sustaining curve [by building a better “X”]. But the prediction of the theory would be that “ABC” won’t succeed with the “X”. They’ve launched an innovation that the existing players in the industry are heavily motivated to beat: It’s not [truly] disruptive. History speaks pretty loudly on that, that the probability of success is going to be limited.

Y was Nokia, ABC was Apple. And X? The iPhone.

Ouch!

Sticking to the tenets of the disruption theory, the Prof assumed that the iPhone was essentially offering a ‘better’ product, not a disruptive product, as it was neither targeting the low-end or unserved customers. He expected that incumbents will copy the features and offer a comparable product. He was further convinced by his belief in a modular product’s ability to beat the integrated product. To this point - the successful launch of Android only further convinced him of iPhone’s imminent doom. Cheaper phones which get the ‘job done’ will take market share from the iPhone. Sounds familiar right.

So what happened? How did the iPhone not only survive but go on to dominate the market?

Ben Thompson, the one-man publishing empire, explains why Prof. Christensen theory fails to account Apple’s success (emphasis mine)

Christensen’s theory is based on examples drawn from buying decisions made by businesses, not consumers.

The reason this matters is that the theory of low-end disruption presumes:

Buyers are rational

Every attribute that matters can be documented and measured

Modular providers can become “good enough” on all the attributes that matter to the buyers

All three of the assumptions fail in the consumer market, and this, ultimately, is why Christensen’s theory fails as well.

Ben suggests that the low-end disruption theory may not be applicable to companies operating in the consumer market - like Apple.

This is because unlike business customers, consumers’ preference for a product may not be ‘rational’ from the price perspective - which is generally the driving force behind business customer’s buying decisions. Just consider IT team buying PCs for its workforce. They are likely to do a cost-benefit analysis and choose a PC which is enough to get the job done. Contrast that with the employees choosing their own PCs - many might prefer high-performance machines with features not necessarily required to complete their jobs but results in better user experience.

In the case of the iPhone - the superior design, better camera performance, fast processor speeds, security environment enriches the overall user experience. However, the user experience is a metric which is not easily measured but matters to the consumer (unlike a business customer buying for the organisation).

Ben has also come up with a new theory to explain the phenomenon. iPhone is not disruptive rather it’s obsoletive.

In short, obsoletion happens when a cheaper, single-purpose product is replaced by a more expensive general-purpose product. Just think about how the phone has obsoleted digital cameras or CD player was obsoleted by the iPod. In essence, what the theory is saying is that - disruption can happen from the top end of the market. It’s not necessary for the entrant to offer a low-end product and then move upmarket. In fact, in the technology world - it’s more likely that the disruption will be top-down.

It certainly is a convincing argument. However, I think there might be a bit more to the story - lets come back to it later in the post. Moving on with Prof. Christensen’s next big prediction

Uber

Most people would say that Uber is a disruptive company. It’s completely changed the landscape of the taxi industry.

Well - here’s the Prof in 2015

Uber is clearly transforming the taxi business in the United States. But is it disrupting the taxi business? According to the theory, the answer is no. Uber’s financial and strategic achievements do not qualify the company as genuinely disruptive

The Prof argues that disruptive innovations originate in low-end or new-market footholds. Uber, however, didn’t originate in either, it offered services to a well-served market (San Francisco). Further, its services were arguably more convenient and of better quality than the incumbents. Thus making the case for Uber to be sustaining innovation.

Here’s a takedown of the above view.

More interesting though is Alex Danco’s alternative narrative - the ecosystem effect. He argues

The ecosystem as a whole may be disruptive, but any given piece of this ecosystem does not really want to compete on price or plug-and-play modularity at the low end. They want to deliver the best experience possible, not compete on cost! They want the best users, not the lousy ones!

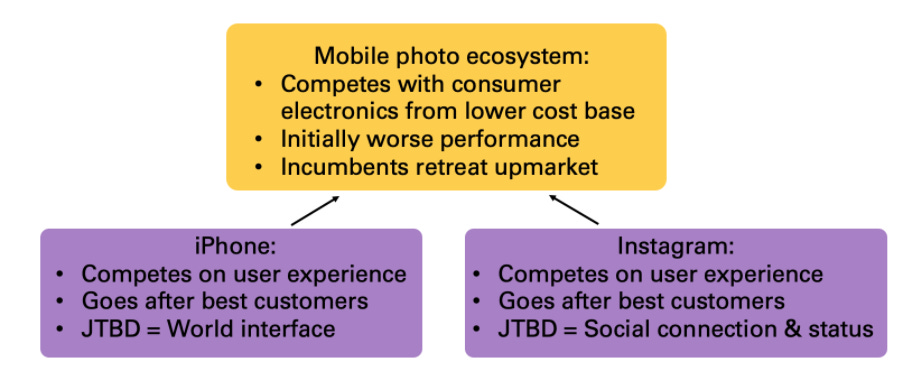

Example of digital cameras being disrupted by the smart mobile photo ecosystem. (image from Alex Danco’s blog)

In other words, the taxi business was not ‘disrupted’ by Uber in the sense that Prof.Christensen means the word. But the whole ecosystem did disrupt the taxi business. The ecosystem powered by google maps and mobile connectivity is modular as the rider can choose Uber / Lyft on either iOS / Android. This also explains the disruption flowing from the top-end at the company level, as they chase the highest quality users by offering the best user experience.

And finally…

Tesla

Here is the Prof’s view on Tesla in 2015

Tesla Motors is a current and salient example. One might be tempted to say the company is disruptive. But its foothold is in the high end of the auto market (with customers willing to spend $70,000 or more on a car), and this segment is not uninteresting to incumbents. Tesla’s entry, not surprisingly, has elicited significant attention and investment from established competitors. If disruption theory is correct, Tesla’s future holds either acquisition by a much larger incumbent or a years-long and hard-fought battle for market significance

Not to rub it in, but here’s Tesla’s market cap comparison as of August 2020

The irony is that - with a market cap of $380b - the only company which can probably afford to buy Tesla is Apple!!

Okay - but hold on a minute. You say - let’s not look at frivolous things like market cap, let’s argue the merits of the case on the product quality, business model etc, etc. and you may be right.

So basically, the Prof was not convinced Tesla is disruptive because it had also entered the market from the top-end - remember the Lotus Elise/Tesla Roadster with a price tag of $100,000. So unlike the low-end rebar market, incumbents have every reason to defend their share in the high-end sports car market. He reasonably believed that the incumbents will take defensive action and Tesla will either be bought out or struggle to gain market share.

Another excellent piece on the topic is Ben Evan’s view here. He argues, Tesla is NOT disruptive, rather its a company doing sustaining innovation. And I agree.

His thesis

First, it (Tesla) does have to learn the ‘old’ things - it has to learn how to make cars at scale with the efficiency and quality that the existing car industry takes for granted, and preferably without running out of cash on the way. But, solving ‘production hell’ is just a condition of entry - it’s not victory. If it can only do this, it’s just another car company, and that’s not what has anyone excited. It’s what the cars are that matters.

Second, Tesla also has to be doing new things that the incumbent car OEMs will struggle to learn. This is not quite the same as doing things that the OEMs’ current suppliers will struggle to learn - is it easy for the OEMs to buy the new things?

Third, those disruptive things need to be fundamentally important - they need to be enough to change the basis of competition, and to change what it is to be a car and a car company, so that it matters if they can’t be copied.

Fourth, in addition to all of these there needs to be some fundamental competitive advantage, not just over the existing car industry but also over other new entrants. Apple did things Nokia could not do, but it also does things that Google cannot do.

The disruption theory argues that a sustaining innovator has very low odds to beat the incumbents. But Tesla is now the largest auto company in the world (by market cap) - surely the market is thinking it’s very likely to succeed. What gives?

To summarise, as per the disruption theory

Apple, Uber and Tesla are sustaining innovators

Sustaining innovators are unlikely to succeed as the incumbents are motivated to innovate and defend their businesses. Either they will beat back the entrant by offering even better services or products at comparable prices, or one of them will acquire the entrant

So what might explain the success of Apple (specifically iPhone), Uber and Tesla?

Perhaps the ‘signalling’ effect of a product is the x-factor

Thorstein Veblen, famous sociologist and economist, coined the term ‘conspicuous consumption’ to mean the practice of purchasing luxury goods (or services) for the sake of signalling the buyer’s wealth in order to attain or maintain a certain social status. Generally associated with luxury goods like Ferrari, Rolex or Cartier.

But signalling effect might actually be much more pervasive as explained by Robin Hanson and Kevin Simler in their book The Elephant Brain.

Here’s a useful summary of the primary arguments from the book

Most of our everyday actions can be traced back to some form of signalling or status-seeking

Our brains deliberately hide this fact from us and others

From the perspective of everyday consumption and the motives that drive them, Messrs Hanson and Simler report below findings

Standard motive: To get useful stuff

Hidden motive: We care a lot about what the stuff we use make us look like and what ‘signal’ they send out to the world about us

Example: Think of a hot sunny afternoon, a perfect excuse for a beer. Multiple choice of products is available to a consumer. But the brand they end up choosing might well be determined by what they want to signal - and this may happen at a subconscious level. One may choose local ‘craft’ beer to showcase they have a refined taste, others may choose ‘exotic’ sounding beer from South America to showcase a sense of adventure while some may just choose the cheapest available option showcasing a value mindset.

We can link this back to Prof.Christensen’s worldview and the ‘job’ that a consumer hires a product to do. In case of beer (pun not intended), the job is not just quenching of thirst but also the signal it sends out to others.

Armed with this insight, let’s re-look the three companies

Apple

Prof.Christensen predicted that the iPhone would be replaced by a modular competitor. To some degree that has come true with Android and the multitude of phones operating on that platform, but the iPhone’s share of industry profits is still massive. As far as the user experience is concerned the high-end phones from Samsung and OnePlus have arguably matched or even exceeded the iPhone. If it was the only ‘job’ that the iPhone was dependent on, then it should not have been able to maintain its market share.

Perhaps we need to question the ‘job’ that consumers hire iPhone for is beyond just the user experience. iPhone is doing some other job so well that other phones are not able to do that job for the customers, maybe not even for a higher price.

Using an iPhone allows the users to signal so many things - they care for design, they care about data security and the fact that they can afford to buy it.

It is like a cultural Schelling Point - a focal point that conveys so many things without having to communicate it.

So how did the iPhone tackle the threats

Sustaining innovation: The theory expects that incumbents will be able to learn to do the additional features. But Nokia and Blackberry were not able to learn the software and build a general-purpose product which ‘obsoletes’ the existing product line

Integrated product: Modular products did, in fact, became available for a lower price point. But they could not replace the signalling ‘job’ done by the iPhone

Thus it seems that the iPhone has managed to thrive by transcending its job profile from a mere phone to something much deeper.

However, a counter-view to this might be what happened with the iMac. As it is difficult to square why the similar ‘signal’ effects weren’t enough to drive a strong market share for iMac.

A couple of reasons that resonate with me are

Apple lost the PC market mainly because the operating system and productivity software battle - which have a huge winner take all effects - was won by Microsoft. Whereas in case of iPhones the iOS along with the app store have created their own network effects

iMac never actually dominated the PC market as it did with iPhones

It would seem that the iPhone fulfils its job of providing a great user experience and signalling. However, iMac while it’s able to fulfil the signalling requirement, failed in fulfilling the user experience fully (impaired by the network effect of Microsoft’s productivity software).

Uber

What about Uber? Clearly, it’s not managed to pull off any such change in its job profile. It’s primarily used to get from point A to B conveniently and whether you use Uber or Ola or the normal taxi - it may not be sending out any ‘signal’ about you as a person.

How did it manage to tackle the threats?

Prof.Christensen reasoned

In Uber’s case, we believe that the regulated nature of the taxi business is a large part of the answer. Market entry and prices are closely controlled in many jurisdictions. Consequently, taxi companies have rarely innovated. Individual drivers have few ways to innovate, except to defect to Uber. So Uber is in a unique situation relative to taxis: It can offer better quality and the competition will find it hard to respond, at least in the short term.

In other words, the competition was not motivated and sophisticated enough to be able to learn the sustaining innovation from Uber and apply it to their products.

Tesla

Finally Tesla. We agree that it is a sustaining innovation which started at the top end of the market- so it should be vulnerable to a response from the incumbents.

Unlike in Uber’s case, the competition is organised, sophisticated and highly motivated to protect its market share.

But Tesla does have one thing in its favour - the signalling effect. Owning a Tesla signals so many things which can’t be measured - care about the environment, support for Elon Musk and his world-changing companies.

The question remains though whether Tesla will be able to overcome its production hell and deliver cars in scale without quality issues - as this goes to the basic job the car is supposed to accomplish

Will it go the iMac way or iPhone way?

The market certainly seems to be thinking the iPhone way - if the market cap is any indication

Higher education industry

Another interesting example to understand the impact of the signalling effect is the higher education industry.

In 2012, Prof.Christensen predicted that online courses would disrupt higher education institutes. Again you can understand how it makes sense- low-cost substitute which offers the same quality and gets the job of learning done.

Even Alex Danco’s ecosystem theory predicts a disruption in higher education

The technology in the form of video platforms have become ubiquitous

An ecosystem of modular companies like Masterclass (or Udemy/Coursera) now chase the best consumers offering a high-quality user experience

If learning is the job - they get the job done exceptionally

Yet the top 20 universities are not necessarily sweating.

Maybe, as Hanson and Simler point out in their book, the job of higher education is beyond just offering learning resources. It’s a way of signalling your intellect in the world. A place to build a network, get a stamp of approval or just goof around campus.

Unless these jobs are also accomplished by the entrants - higher education is unlikely to be disrupted.

Okay - now we are in a position to frame when Disruption theory is applicable

Disruption theory still valid as exceptions only prove the rule, however, we need to beware of the exceptions

The basic tenets of the theory still ring true to me. I feel that it offers an elegant framework to understand a company’s strategy and offers useful tools to the incumbents to safeguard their businesses.

However, its certainly not a comprehensive theory which accounts for every scenario and every company. I think we can build on learnings from other new-age strategy thinkers to arrive on the best course of action on a case-by-case basis.

And then - we could use below tests to ascertain if a company is disruptive

And finally - time to put Afterpay through this framework…

Afterpay may be a textbook case of disruption as defined by Prof. Christensen

The ASX is now considered one of the best places for fin-tech companies to get listed. So much so that many US companies now consider listing here. Arguably the brightest star of the ASX’s fintech cohort is Afterpay offering ‘the buy now pay later’ services.

Since listing in 2016 the market capitalisation of Afterpay has grown from $125 million to an eye-popping $25 billion. (In fact its moved up by $3b in the time it took to edit this post)

So is Afterpay actually a disruptive company?

Step 1: Applicability

We can see that Disruption theory will be applicable to Afterpay. As the signalling effect for the business will be relatively low

Step 2: Let’s apply the tests

Test 1: Targeting low-end customers or underserved customers

Yes. Afterpay provides zero cost loans to its customers. Further, its user base is dominated by the younger cohort (18-25 years old) who have been underserved by the credit card companies (incumbents)

Test 2: Has it re-invented the business model?

Yes. Afterpay does not make money like a regular lender. Instead of charging any interest on the loan, Afterpay makes money by charging a fee to the merchants.

Test 3: Has it moved up-market?

This has not yet played out. Currently, the average balance of an Afterpay account is c.$220 whereas the average balance for credit cards is c.$3,500. Also, Afterpay seems to be more focussed on establishing a market share in the US and UK (at the lower end) and continue to build its merchant network.

So looks like Afterpay might become a textbook case of a disruptive company - but its journey is not yet complete.

The company’s biggest threat at the moment though might not be from the incumbents but from the regulators. ASIC is expected to release its findings on the BNPL (buy now pay later) sector in October. Currently, Afterpay and others in the sector are exploiting a loophole in the law which ensures that they are not regulated as credit providers!

Plenty of interesting things on the horizon in this sector - but that will have to wait for the another post :)